Unit Testing

August 15, 2018One of the most important (and most ignored) aspects of programming is testing.

However, especially within academic backgrounds, the typical coding cycle is

- Throw together messy, but entirely functional code

- Run code a single time before abandoning it entirely

- Realize months later said code can be adapted for a slightly different purpose

- Struggle with debugging minor changes not having desired effects

- Rewrite or copy entire blocks with minor name changes to just get it working

- Arrive at different set of messy, but entirely functional code

Breaking out of this cycle is a difficult, but extremely worthwhile endeavor! One of the best ways to help improve this is by practicing unit testing. The idea is two-fold:

- Break code into small, single-purpose functions (units)

- Write tests to ensure each unit behaves as desired

With this setup, you develop individual components which can be pieced together for more complex algorithms. Clearly, this is more effective than increasingly long singular code blocks! Plus, your functions become far less susceptible to unexpected errors. However, this requires you don’t touch the function once it is working as intended!

Okay, that might be a bit too strong, but at least try not to touch it! In general, it will take some work to figure out the exact setup for whatever program or analysis you’re trying to achieve. But once you establish a framework that fits your purposes, you should keep those fundamental parts of your code base unchanged.

An Example from the SWITRS Data

For this post, I am going to explore a situation I encountered through my Collision Analysis project, and work through how to best approach it with a unit testing mindset. This will mean undertaking the following actions:

- Split desired goal into single-purpose, immutable functions

- For each function, identify error-producing inputs and special case outputs

- Establish individual tests for these cases and validate each one is correctly passed

An excellent way of handling testing in python is using the package pytest (along with ipytest to easily run tests within Jupyter notebooks).

This package makes it very easy to establish tests, run through a variety of inputs for each one, and quickly validate the results across the entire module.

There are also nice ways of setting up such checks to run in preparation for committing code changes, or at the beginning / end of any coding session.

Problem Setup

Now let’s take a closer look into the situation. To see the full code used in this post, check out the Testing notebook.

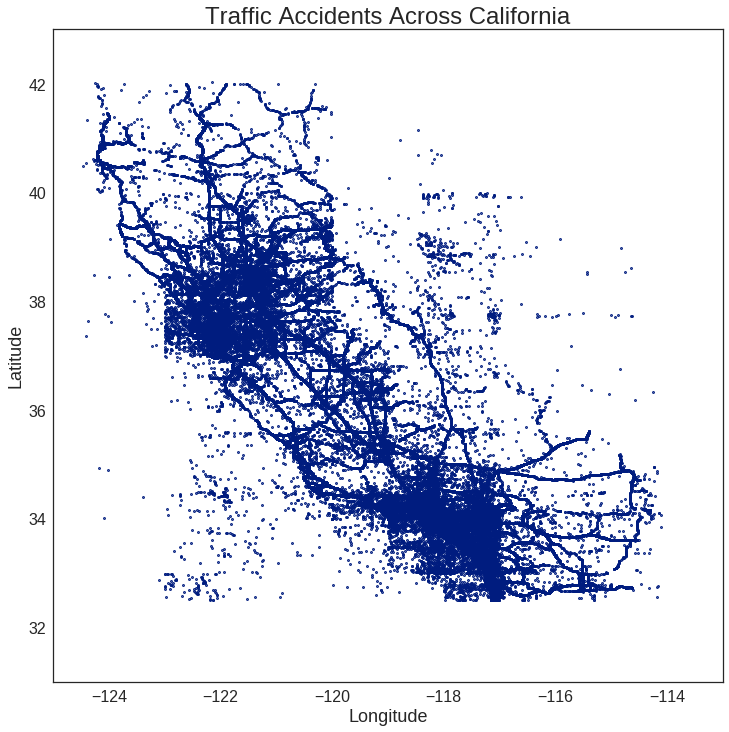

Each of the data points in the SWITRS dataset represents a car accident as documented by the California Highway Patrol. The problem is, many of these locations were improperly recorded in their Latitude / Longitude (unless the CHP jurisdiction extends into the ocean…). The following shows the unmodified GPS data for these collisions, where each blue point is a single accident report.

Even without drawing the borders of California, there are enough accidents to roughly discern its boundary, and to note the anomalous points in the NE and SW regions. There also seem to be some unnaturally square regions around San Francisco and Los Angeles, but we’ll ignore those for now. The goal is to use a boundary which roughly matches the area of California and filter out accidents which clearly lie outside this region.

Note: I originally used geopy to specifically identify the location of each coordinate pair, but this took around 1 second for each entry.

With several hundred thousand points for each year in the SWITRS dataset, this was not a feasible method.

Instead, I needed something which quickly filters out the clearly wrong points, like those in Nevada or the Pacific Ocean.

Approach

In order to classify points as being in_bounds or not, we need a way to define the bounds, as well as a method of testing each set of coordinates against them.

To make it simple, we’ll only use straight lines to indicate boundaries.

This means each boundary line is defined by two points, and the entire figure by a closed list.

For instance:

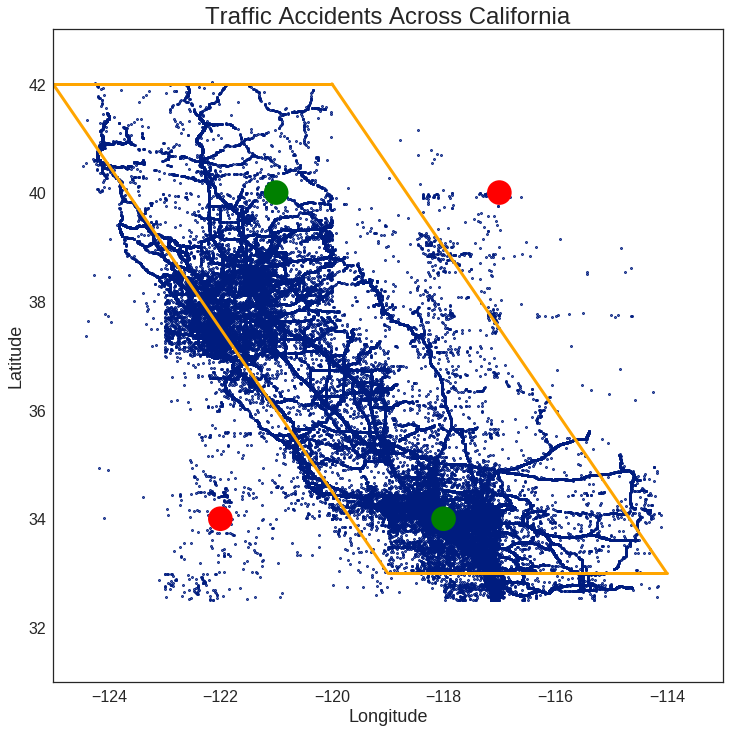

bounds = [

(42, -125),

(33, -119),

(33, -114),

(42, -120),

]

The boundaries are shown in orange, with the green (True) and red (False) test points indicating whether each one should be considered in_bounds.

Eventually, this can be extended to any arbitrarily complicated shape desired (as long as it’s defined by straight lines). For now, even a simple test case is fine, as utilizing proper unit testing will give us confidence that nothing will break for a more complex case.

With the boundaries defined, my plan for checking each set of coordinates is as follows:

- Find the slope and intercept of each boundary line segment

- Identify whether coordinates are above or below each line segment

- Confirm coordinates are correctly above / below all line segments

If a point is correctly located relative to each line segment, consider it in_bounds.

Step 1 - Find the Slope / Intercept of a Line

Before starting to write the actual code, let’s take a moment to consider its structure. This includes its purpose, inputs, outputs, and the unit tests we will need to consider.

‘Slope of Line’ Function

Determines the slope and intercept of a line formed by two points.

Input:

p1 (tuple: (float, float)) - 1st point in the form (x, y)

p2 (tuple: (float, float)) - 2nd point in the form (x, y)

Output:

m (float) - slope of line

b (float) - intercept of line

Error-based Tests

- Check for invalid input

- Null arguments

- Non-tuple arguments

- Too few arguments

- Too many arguments

- Non-castable arguments

- Check identical points (undefined slope)

- Check purely vertical points (infinite slope)

Special Case Tests

- Check purely horizontal points (zero slope)

- Check mirrored points for equality

With this information in hand, writing the function itself is effectively a direct transposition of these criteria.

def get_line_eq(p1, p2):

""" Determines the slope and intercept of a line formed by two points.

Input:

p1 (tuple: (float, float)) - 1st point in the form (x, y)

p2 (tuple: (float, float)) - 2nd point in the form (x, y)

Output:

m (float) - slope of line

b (float) - intercept of line

"""

# List of potential error messages

err_input_syntax = "Error: each point must be a tuple of floats in the form (x, y)."

err_identical_points = "Error: identical points entered for p1 and p2."

err_infinite_slope = "Error: slope is infinite, and has no valid intercept."

# Check validity of input parameters

try:

x1, y1 = [float(p) for p in p1]

x2, y2 = [float(p) for p in p2]

except (TypeError, ValueError) as Error:

raise Error(err_input_syntax)

# Check for identical points (undefined slope and intercept)

if (x1 == x2) and (y1 == y2):

raise ValueError(err_identical_points)

# Check for vertical line (infinite slope and no intercept)

if x1 == x2:

raise ValueError(err_infinite_slope)

# Otherwise, return standard calculation from line formula

m = (y1 - y2) / (x1 - x2) # Slope

b = y1 - m * x1 # Intercept

return m, bNow, let’s start setting up tests! To make it simpler, I generally start by defining some valid and invalid inputs. The invalid ones cover a variety of null, uncastable, and incorrect length arrays. (Are there any important cases I missed…? Let me know!)

_p1 = (1, 1)

_p2 = (2, 2)

invalid_vals = [

None,

(),

(1),

((1, 2), None),

((1, 2), 3),

('test', 1),

(1.5, 1.5, 1.5),

((1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)),

]Each of these need to be passed into the various testing functions.

In order to do this more easily, we use pytest.mark.parametrize to pass in entire arrays.

From this, all possible combinations of inputs are looped over when running the actual tests.

@pytest.mark.parametrize("p1", invalid_vals + [_p1])

@pytest.mark.parametrize("p2", invalid_vals + [_p2])Error Testing

Now let’s construct a test which checks to make sure all of these invalid inputs cause the function to fail in a predictable way.

From how we defined get_line_eq above, this should raise either a TypeError or ValueError.

However, one of the combinations of p1 and p2 used is with both valid inputs (_p1 and _p2), and should not fail.

In order to account for this, I add a quick check to skip this input case.

Note: testing function names are required to start with test_ in the pytest framework.

def test_input_errors(p1, p2):

# Ignore base case

if p1 == _p1 and p2 == _p2:

return

with pytest.raises((TypeError, ValueError)):

get_line_eq(p1, p2) Running this test function through pytest produces the following output:

============================= test session starts ==============================

platform linux2 -- Python 2.7.13, pytest-3.0.5, py-1.4.32, pluggy-0.4.0

rootdir: *hidden*/notebooks, inifile:

collected 81 items

Testing.py .................................................................................

========================== 81 passed in 0.19 seconds ===========================

Hooray!

As hoped, our tests appear to be running successfully, and none of the invalid inputs are returning values without causing errors.

The 81 tests come from all the possible values from the parametrize lists, as there are 8 values in invalid_vals and 1 for each of _p1 or _p2 ().

Note: skipping over the (_p1, _p2) case automatically counts as a success.

Now, let’s construct the other error-based tests which look for an undefined or infinite slope.

Rather than the invalid inputs of the previous test, we can use our properly defined points in order to make these checks.

This means there is no need for the parametrize decorators.

def test_identical_points():

with pytest.raises(ValueError):

get_line_eq(_p1, _p1)

def test_infinite_slope():

with pytest.raises(ValueError):

get_line_eq((_p1[0], _p1[1]), (_p1[0], _p2[1]))Value Testing

Moving onto the remaining tests, we now want to check what happens actual values are returned.

Rather than using the pytest.raises function as above, we now utilize the assert functionality of python.

This raises an error if the specified condition is not satisfied.

Typically, this ends up being in the form assert (a == b), but for this case I prefer np.isclose to avoid any issues with floating point rounding.

Again, we setup a variety of cases in order to check any situations which may arise. Some of these may end up being a bit redundant, but since the testing process takes less than a second, it is not a concern at this point.

For this case, I utilize an alternative format for the parametrize function which takes in an entire set of inputs at once.

As a result, pytest only checks the specified combinations instead of looping over all possible values.

@pytest.mark.parametrize("p1, p2, m, b", [

(( 2.0, 2.0), ( 3.0, 3.0), 1.00, 0.00), # Positive Slope

(( 0.5, 2.0), ( 3.5, 5.0), 1.00, 1.50), # Positive Intercept

((-2.0, 2.0), ( 3.0, -3.0), -1.00, 0.00), # Negative Slope

(( 6.5, 4.5), (-3.5, -6.5), 1.10, -2.65), # Negative Intercept

(( 3.0, 5.0), ( 7.0, 5.0), 0.00, 5.00), # Zero Slope

])

def test_slope_values(p1, p2, m, b):

(m_check, b_check) = get_line_eq(p1, p2)

# Account for floating point precision when running tests

assert np.isclose(m, m_check) and np.isclose(b, b_check) Lastly, we need to confirm the order of points has no effect on the actual result.

Again, we use np.isclose to ensure floating points issues are not interfering with our testing.

def test_mirrored_points():

m1, b1 = get_line_eq(_p1, _p2)

m2, b2 = get_line_eq(_p2, _p1)

# Account for floating point precision when running tests

assert np.isclose(m1, m2) and np.isclose(b1, b2)Re-running the testing module again returns successful results!

============================= test session starts ==============================

platform linux2 -- Python 2.7.13, pytest-3.0.5, py-1.4.32, pluggy-0.4.0

rootdir: *hidden*/notebooks, inifile:

collected 89 items

Testing.py .........................................................................................

========================== 89 passed in 0.20 seconds ===========================

For the other two functions, I follow the same basic outline as above. To check the inputs of each variable, I generally use the same list of values as above, as they provide a good coverage of the potential ways the functions could break.

If you wish to see the actual code and the corresponding test functions for these cases, they are found in the Testing notebook.

Step 2 - Identify if a Point is Above or Below a Line

‘Above Line’ Function

Checks whether an coordinate is above the line defined by .

Input:

x (float) - x-coordinate of point to check

y (float) - y-coordinate of point to check

m (float) - slope of line to compare

b (float) - intercept of line to compare

inclusive (bool) [optional] - whether equality counts as above

Output:

above (bool): true if (x, y) coordinate is above line defined by y = mx + b

Error-based Tests

- Check for invalid input

Value-based Tests

- Check

inclusivebehaves properly when on line - Check positive / negative slopes and intercepts

Step 3 - Check if a Point is Within Bounds

‘In Bounds’ Function

Checks whether the given coordinates lie within a specified closed boundary.

Input:

coords (tuple: (float, float)) - coordinates to check in form (lat, lng)

bounds (list: tuple: (float, float)) - coordinates defining line segment

end points in form (lat, lng)

line_checks (list: bool) - whether point should be above each line segment to be

considered within the boundary

Output:

in_bounds (bool) - whether coords lies in area defined by bounds

Error-based Tests

- Check for invalid input

- Check for identical bounds / check lengths

- Check for valid Latitude / Longitude values

Value-based Tests

- Check the four initial test values

Final Results

After validating all the unit tests are working properly, we can have confidence in the performance of our functions across any inputs. However, it is important to remember the functions and their tests should remain unchanged unless some sort of error is discovered. Any extended usage related to this idea should be made with new code which calls these basic functions.

Now!

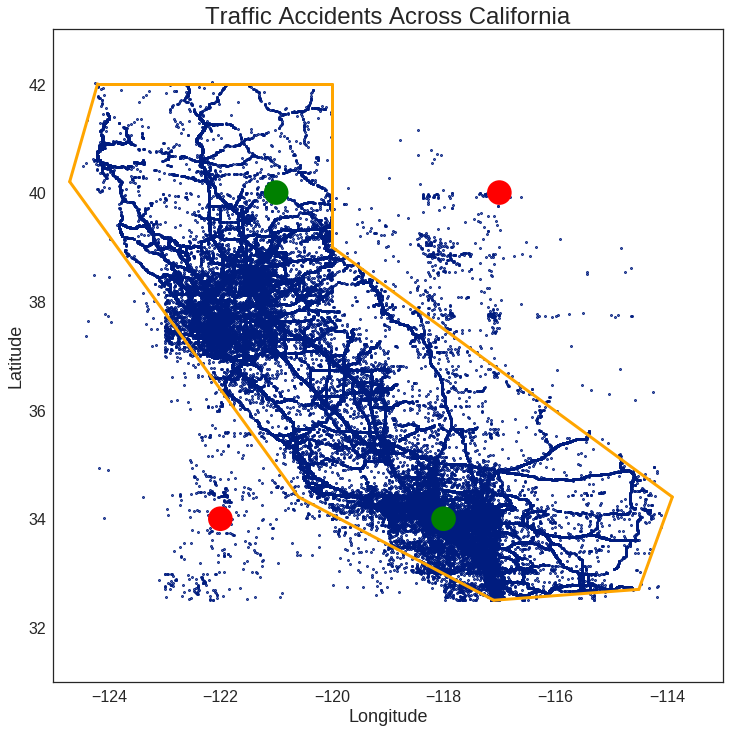

It’s finally time to use a more sophisticated boundary for the in_bounds check.

Using the code on the Mapping notebook, I decided the following boundaries well-approximate the area of California.

Note: it may not look precise on the plot, but the boundaries on a map are more convincing!

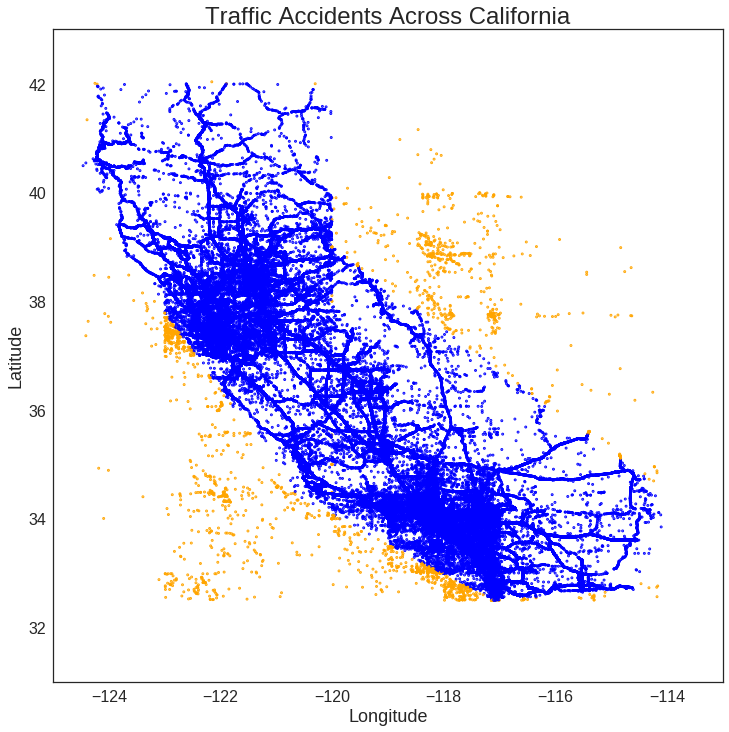

Using these new boundaries, we then run the in_bounds check across each collision entry.

Amazingly, even with over 800k entries, the entire process only takes about a minute in total.

Color-coding the results (blue: True, orange: False), we see the function is indeed working as intended!

Conclusion

Taking the time to setup the boundary check in the context of unit testing proved exceedingly valuable for this task. Namely, setting up the structure for each individual function made it easy to translate into actual code. By ensuring all possible inputs are being appropriately handled, we are confident that both simple and complex use cases give correct results.

The testing itself also didn’t require any overly complicated checks, as we built up each individual step in a simple, reliable way. If we are good about leaving them unchanged, we can have confidence these functions will continue performing as expected going forward. If for some reason any of the functions do get changed, the unit tests still provide guidance for debugging any potential issues that may have occurred in order to reconstruct their intended usage.

As a result, through unit testing, we have successfully developed a quick method to perform a relatively complicated check with solid confidence in its accuracy!